INTRODUCTION

Obesity is becoming the most dangerous lifestyle disease of our time, and its effects are already being observed in both developed and developing countries. Obesity can be described as an increase in the adipose tissue that releases a wide variety of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, called adipokines, promoting inflammation, recruitment of macrophages and insulin resistance. Multiple etiological factors have been attributed to the genesis of obesity, of which hereditary predisposition, wrong dietary habits and life-style (lack of exercise) , besides change in the gut microbiome composition also play another vital role in genesis of obesity.

Human gut is the habitat of diverse and dynamic microbial ecosystems. The collection of bacteria, archaea and fungi inhabiting in the human gastrointestinal tract is termed as ‘Gut microbiota’. A biological mutualism relationship exist between gut microbiota and host. The number of microorganisms inhabiting the GI tract has been estimated to exceed 1014, which encompasses ∼10 times more bacterial cells than the number of human cells and over 100 times the amount of genomic content (microbiome) as the human genome.

The microbiota offers many benefits to the host, through a range of physiological functions such as

- Strengthening gut integrity or shaping the intestinal epithelium

- Regulating host immunity

- Produce substances that are antifungal, antiviral and antibacterial & reduce the risk of infections.

- Produce substances such as antidiabetic, anticancer, antiobesity, stress(mental and physical), anti asthma, anti chronic pulmonary

- Strengthen intestinal barrier system & prevent allergy and hypersensitivity reactions.

However, there is potential for these mechanisms to be disrupted as a result of an altered microbial composition, known as dysbiosis(or an imbalance between commensal and pathogenic organisms). Healthy microbiome, can vary distinctly between gender, across different ages, geographical regions and medical contexts.

Recently, it has been observed that the composition of gut microbiota of healthy persons is different from that of obese ones. Such observations suggested a possible relationship between the compositional pattern of gut microbiota & pathology of metabolic disorders. Currently, advanced technique for bacterial DNA sequencing & bioinformatics tools have contributing to identify bacterial communities in various orders. Phyla constitute the highest level of classification, which is sequentially subdivided into class, order, family, genus and species. The most predominant phyla (90%) in human gut microbiota are phyla, Bacteroidetes (Gram negative), Firmicutes (Gram positive) and Actinobacteria (Gram positive), are most abundant and have been found to play a dominant role in the pathophysiology of metabolic disorders specifically, obesity. Other phyla also contribute, but to a lesser degree.

DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN GI MICROBIOTA

The composition of gut microbiota is unique to each individual, just like our fingerprints. Composition of gut microbiota starts to define each individual from beginning of the birth, through several factors such as mode of delivery (caesarean delivery vs. vaginal delivery), breast milk vs. formula feeding, antibiotic usage, and timing of the introduction of solid foods and diet.

MODE OF DELIVERY

For vaginally born infants, Lactobacillus (phyla Firmicutes) dominates the gut, but within months there is a greater distribution of Bifidobacterium (phyla Actinobacteria) and Bacteroides (phyla Bacteroidetes) microbiota composition. High abundance of lactobacilli during the first few days, is due to a reflection of the high load of lactobacilli in the vaginal flora. Within the Lactobacillus genus, different species are associated with an obese profile (Lactobacillus reuteri) or a lean profile (Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus plantarum), such that the microbiota composition is related to body weight and obesity at the species level.

In contrast, the gut microbiome of an infant born by caesarean section are comprised of a bacteria that are transferred horizontally from the mother’s and others’ skin surfaces. Infants born by C-section have a low bacterial diversity. They have lower proportions of Bifidobacteria(phyla Actinobacteria) and Bacteroides(Bacteroidetes phyla) compared to vaginal born infants & are dominated by Staphylococcus(phyla Firmicutes) & facultative anaerobes such as Clostridium species.

Being born by C-section is related to an 11% higher risk of obesity. Compared with the control mice, C-sectionborn mice lack the dynamic developmental changes of gut microbiota. Here, they found that the bacterial taxa which are related to vaginal delivery, such as Clostridiales, Ruminococcaceae(Firmicutes) and Bacteroides(Bacteroidetes) have previously been related to lean phenotypes in mice. The results prove that there is a causal relationship between C-section and weight gain and could support that maternal vaginal bacteria participation in the normal metabolic development of offspring.

SOLID FOOD

Studies have shown that major shifts in the taxonomic groups of the microbiome have been observed with changes in diet such as weaning to solid foods. The introduction of solid food to the breastfed infant causes a rapid rise in the number of microbial composition in the gut such as enterobacteria and enterococci, followed by progressive colonization by Bacteroides (Bacteroidetes), Clostridium, and anaerobic Streptococcus(Firmicutes).

In formula-fed infants, however, the transition to solid food does not have as great an impact on gastrointestinal flora. As the amount of solid food in the diet increases, the bacterial flora of both breast and bottle-fed babies approach a more stable community composition characteristic of the adult microbiota.

DIET

Beyond the transition to solid foods, we know that types of food and dietary habits also influence our gut microbiome. Gut microbes depend on the host diet to survive and harvest energy. The metabolic activities of the gut microbiota facilitate the extraction of calories from ingested dietary substances, help to store these calories in peripheral tissues(liver, adipose tissue, etc) for later use, and provide energy and nutrients for microbial growth and proliferation. It has been suggested that a person’s gut microbiota has a specific metabolic efficiency and that certain characteristics of the microbiota composition might predispose to obesity.

The composition of intestinal microbiota is strongly affected by dietary patterns, high fat, high sugar& western diet intake was associated with 20% growth of Firmicutes & 20% reduction in Bacteroidetes. The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B) differs between obese and lean humans, with lean people having higher Bacteroidetes and fewer Firmicutes than obese individuals.

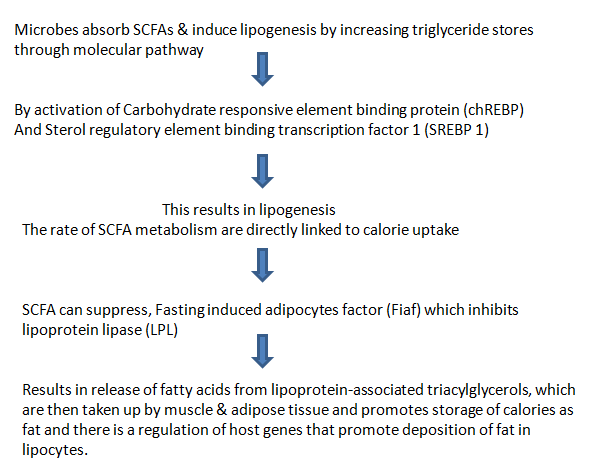

SHORT CHAIN FATTY ACIDS (SCFAs) AND OBESITY

Firmicutes breakdown carbohydrates in the gut, which can’t be digested by body’s enzymes such as dietary fibre & resistant starch, they ferment & produce metabolites, Short chain fatty acids(SCFAs),that are either absorbed by gut or excreted in feces.

CHRONIC SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION AND OBESITY

On the basis of the recent demonstration that obesity and insulin resistance are associated with low-grade chronic

systemic inflammation, Cani et al postulated another mechanism linking the intestinal microbiota to the development of obesity. They hypothesized that bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from gram-negative bacteria residing in the gut microbiota acts as a triggering factor linking inflammation to high-fat diet–induced metabolic syndrome.

Gut microbiota also may contribute to metabolic disturbances observed in obese patients by triggering systemic inflammation. In a series of experiments mice fed with high-fat diet, they showed that (1) a high-fat diet increases endotoxemia and affects which bacterial populations are predominant in the intestinal microbiota, favour an increase in the gram-negative to gram-positive ratio), (2)chronic metabolic endotoxemia induces obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes.

CONCLUSION

Certain metabolic products of gut microbiota, such as propionate & butyrate also play a vital role in maintaining proper body weight. Microbiome modulators (e.g. antimicrobials, diet, prebiotics or probiotics) mostly aimed to replace some of the defective microbes and specific commensal strains, probiotics, defined microbial communities, microbial-derived signalling molecules or metabolites helps to restore the healthy gut microbes by regulating normal metabolic process. Given the contribution of host genetics in many diseases associated with a dysbiotic microbiota, dual therapeutic strategies (e.g. combining immunotherapy and microbiota-targeted approaches) may also be required to restore the environment required to re-establish an effective communication between the host and the targeted microbiota.

Reference

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025619611607027l

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2648620/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X14609769